Hansen’s Disease and Family: Reflections on Reading and Teaching Mugi baa no shima (Grandma Mugi’s Island) Part1

/Kathryn Tanaka (Otemae University)

In 2001, a group of Hansen’s disease survivors won a lawsuit against the Japanese government that argued that health policies targeting Hansen’s disease violated their human rights. The victory was the culmination of decades of social and political activism on the part of survivors. Yet, as recent lawsuits by relatives of survivors demonstrates, there are continuing traumas caused by Japanese policies. In the wake of the 2001 lawsuit, a story of total quarantine and survivor struggle against the governmental violation of their human rights began to solidify. Today, complicating this heretofore dominant narrative is part of the process of cultural memory making and reconciliation of the issues surrounding Hansen’s disease in Japan. Furthermore, the importance of literature and the passing of stories from survivors to the next generation is an integral but often overlooked part of this process.

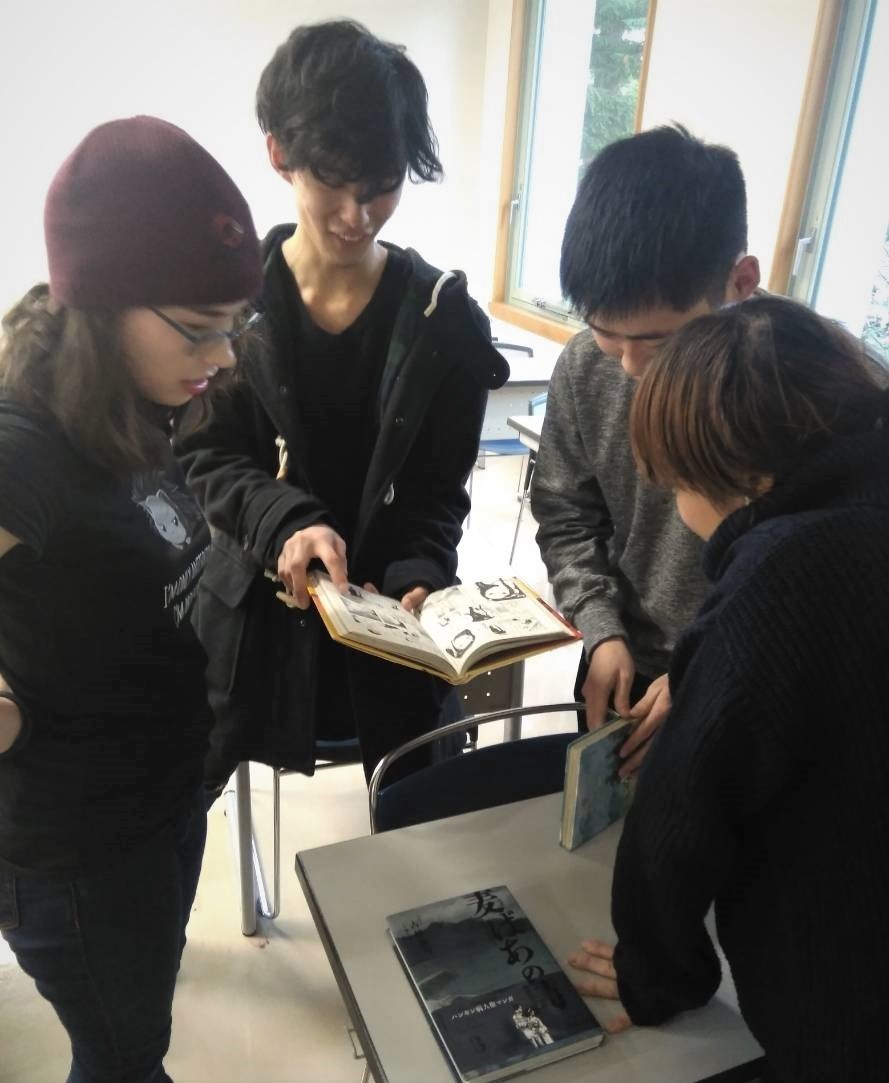

As the age of survivors increases, the testimony and the stories they have worked hard to preserve have become the subject of popular narratives by authors who did not experience the illness or quarantine. Such works are sometimes criticized for appropriation of survivor experience for sensational ends, but this dismissal overlooks questions of how stories are borrowed, retold, and integrated into a broader, national discourse.

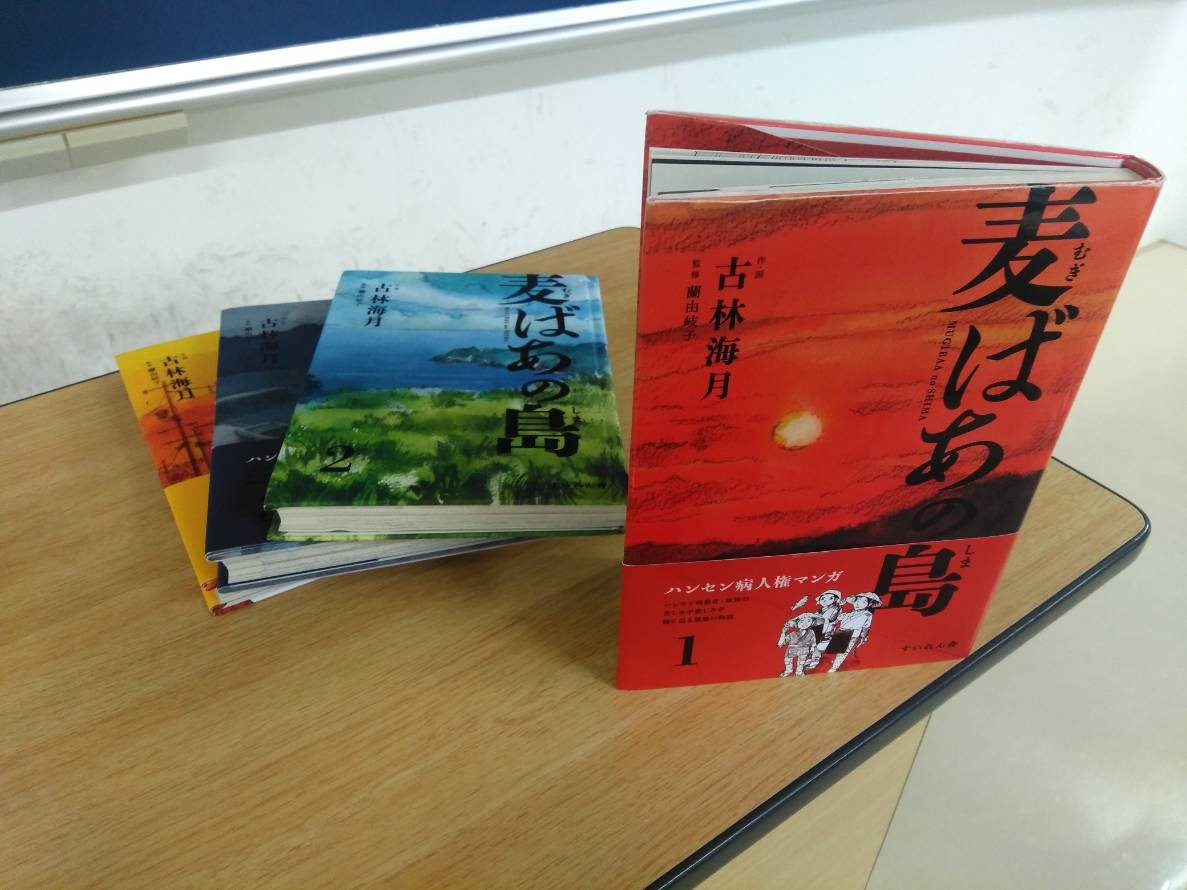

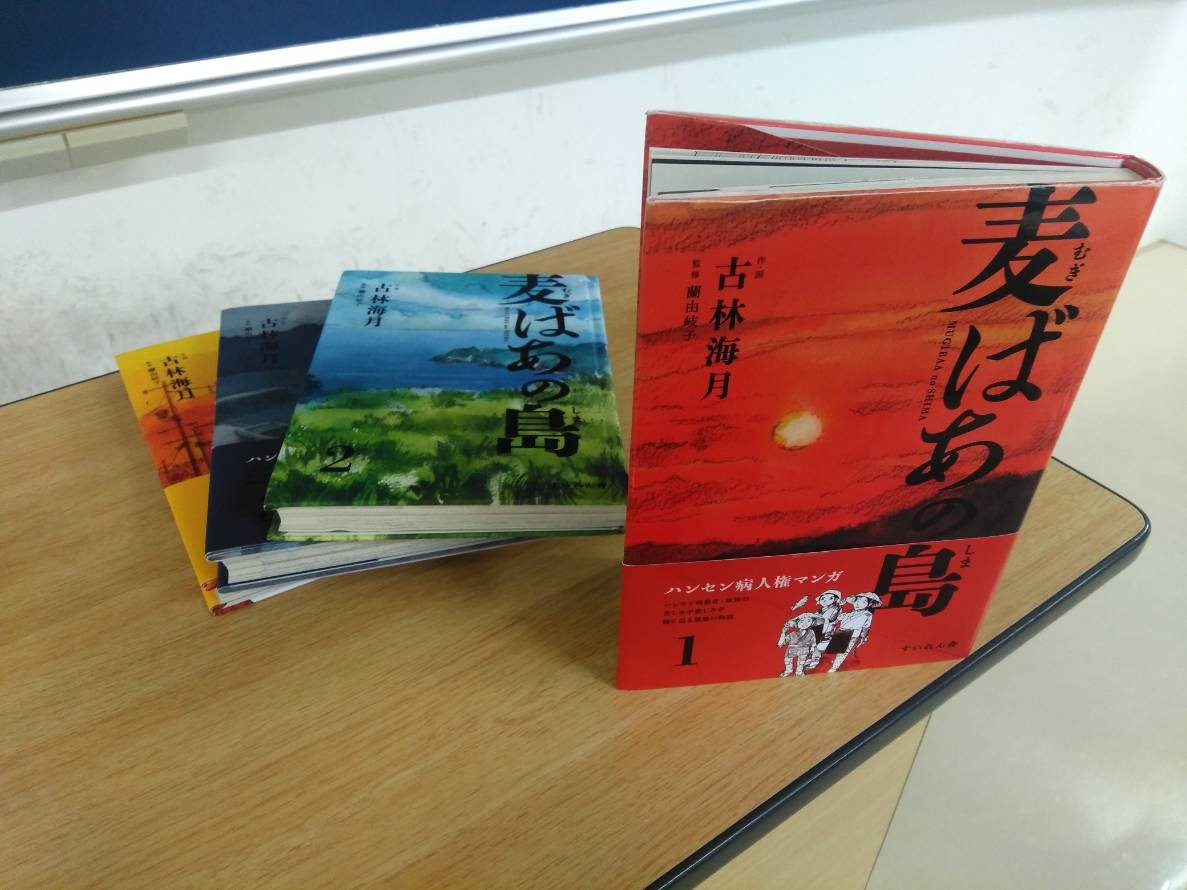

Two recent examples of fictionalized accounts of Hansen’s disease have gained broad attention. The first is a four-volume manga, drawn and written by Furubayashi Kaigetsu with direction from sociologist of Hansen’s disease, Professor Araragi Yukiko of Otemon University, Mugi baa no shima (Grandma Mugi’s Island, Suiren-sha, 2017). The second is Dorian Sukegawa’s acclaimed novel that was made into a popular movie, An (Sweet Bean Paste, 2015 & English translation by Alison Watts, 2017). These works share a great deal in common: both are structured around the figure of a female survivor relating her story to two other people. In the case of An, the story is told by a survivor Tokue to an older man, Sentaro, and Wakana, a young girl in junior high school. Mugi baa no shima also takes a female survivor as its focal character; in this 4-volume manga, Uehara Mugi relates her experiences to two sisters, Satoko and Shiori.

These two tales share much in common: In both cases the authors did years of visits and wrote based on multiple conversations with survivors, which certainly gives nuance to their depictions of the experience of Hansen’s disease and social discrimination. Again, both stories include the narration of the story of Hansen’s disease from a survivor to people outside the sanatorium. But both accounts share other features as well: the narration takes place within a pseudo-family structure. That is, in both cases, the survivor tells her story to an adopted family, a family who is bound by circumstances other than blood. In the case of An, the characters share the experience of isolation: Tokue, in quarantine; Sentaro, as an ex-convict; and Wakana, who is dealing with a dysfunctional home life from which she struggles to escape. In Mugi baa no shima, rather than treating “isolation” as a theme which binds its characters, the author has crafted a manga that connects Hansen’s disease to issues of fertility and womanhood.

While there are many other points about An that deserve attention, I’d like to focus on what makes Mugi baa no shima an important contribution not just to Hansen’s disease studies, but to a broader dialogue about family and motherhood in Japan. The manga is set in Himeji in the mid-1990s. In its opening pages, we meet Satoko, a college student, who has come to an obstetrics and gynecology clinic for an abortion; we also met Satoko’s sister Shiori, who is undergoing fertility treatments to try and conceive a child. Finally, we meet Uehara Mugi, who runs a hair salon near the clinic and is a Hansen’s disease survivor.

Over the course of the 4 volumes, Mugi relates her story to Satoko and Shiori. She tells them of her diagnosis with the illness as a child, and her subsequent separation from her family and quarantine. Through her experiences and the experiences of the people she meets we learn history of Hansen’s disease in Japan as it intertwines with personal experience. We hear stories of the laws passed in Japan, and the different institutions, such as Osaka’s Sotojima Hoyoin, an institution that was destroyed by a typhoon. Through this, we learn the history of the institution where Mugi lived, Okayama’s Oku Komyō-en. The legal, medical, and social experiences of the illness, however, are grounded first and foremost in personal stories and shared experiences.

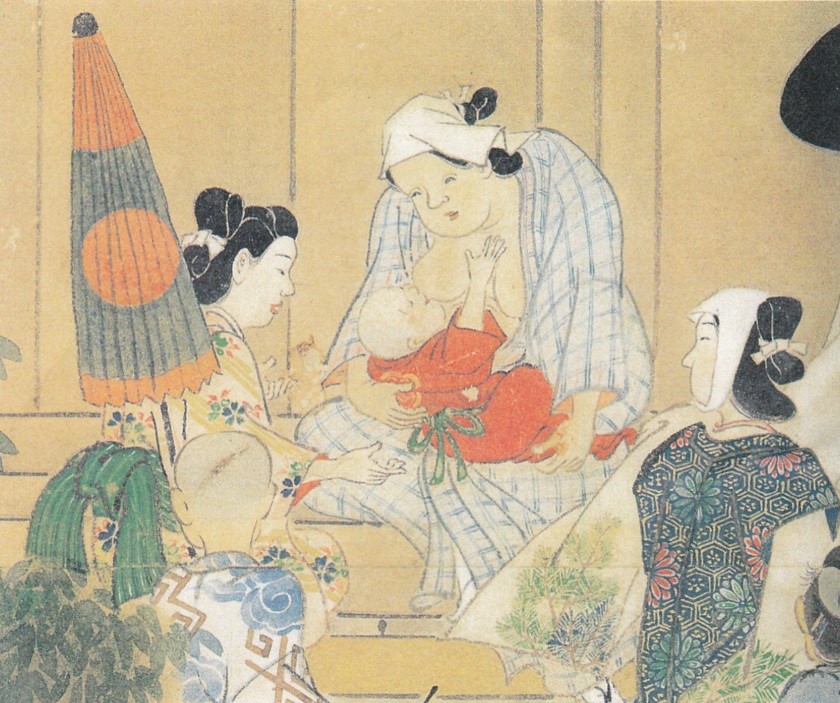

As we read Mugi-baa’s story, we see how ties to siblings and natal family change in very different ways depending on the member. We see other residents in the institution struggle with their family relationships. The manga carefully depicts a variety of relationships inside and outside the institution, and as delicately charts how families and friendships change from multiple perspectives. The points that the artist and author weaves together are intricate and brilliantly done. As Mugi continues her story of her past life, we also read of her meeting her husband, falling in love, getting married, and getting pregnant—which was not allowed at the facility and ends in a forced abortion.

As the story unfolds, the reader is invited to connect the stories of Mugi, Satoko and Shiori as they see the three of them becoming a family. In doing so, they also connect Hansen’s disease to broader questions of what it means to be a family as well as modern social problems such as fertility and multiple forms of motherhood. One of the strengths of the manga is that while it makes the questions and the strong, familial relationships clear, it offers no easy resolution to the social problems it also addresses.

The text is haunted by the ways in which women become mothers without babies: through abortion, through miscarriage. The stone figurines, jizō, that represent the children who were not born serve as potent, physical reminders that each woman has had a child but all are united in the loss of their children: by choice, by force of man, or by force of nature. This centering of absent children, echoed throughout the text helps create the firm connection between Hansen’s disease policies and other, current social issues in Japan and abroad: decreasing birth rates, increasing infertility, and the question of what is a family and who makes a family. As Shiori remarks in the text when she recounts holding her daughter in the hospital after her stillbirth: “Just for that moment, while I was there, I became a mother” (171, vol. 4). And hearing the story, Satoko realizes: “Grandmother Mugi and my sister were both mothers” despite the fact neither has a living child (173, vol. 4). And when Satoko blames herself, saying there is a difference because she made a choice while the other two women had none, Mugi simply says: “It’s not different” (178, vol. 4), and later tells her: “You’ll be alone but you won’t be alone. Because you are also a mother” (183). And the reader watches Satoko grow and make peace with her choices, finally naming the jizō that represents her lost child Komugi (Little Mugi), “because if it’s my child, that’s like being Grandmother Mugi’s great-grandchild” (193, vol. 4). The absent children bind the women together as a family of mothers without children.

In addition to the absent children, it is knowing each other’s stories that binds them together. When Mugi’s brother angrily appears at her salon because she is advertising it in the local community, he remarks: “You’re a person that should have been dead” (130, vol. 3). When Satoko grows angry at him, he tells her to mind her own business as she has nothing to do with his relationship to Mugi. Satoko, says, “I don’t know anything [about your family], and I’m not part of it… I’m an outsider but! I’m more of a relative than you!” (132, vol. 3). She follows up with: “You may be her younger brother but I won’t allow you to bully Grandmother Mugi!” (134, vol. 3). Family, we see, is bound by shared experience rather than blood—a lesson reinforced when the act of Mugi cutting her brother’s hair renews their childhood memories and seems to offer the potential to start to heal their relationship in the present (137-152, vol. 3).

In a way, the novel is also about Satoko’s coming of age, and her learning the importance of family. It is that parallel story that makes this a rich, multivalenced text with broad appeal. While the question of the story of Hansen’s disease is central to the text, the tangential issues it raises is what makes this an incredibly rich and important text not just for Hansen’s disease, but for questions of womanhood and family in Japan.

Arai Yuki, Kakuri no bungaku: Hansen-byō ryōyōsho no jiko hyōgen-shi [Literature of Quarantine: A History of Self-Expression in Hansen’s Disease Sanatoria]. Shoshi arusu, 2011.

Araragi Yukiko, “Yamai no keiken” wo kikitoru: Hansen-byō-sha no Raifu Stori [Hearing the “Illness Experience:” Life Stories of Hansen’s disease survivors] [New Edition], Seikatsu shoin, 2017.

Hirokawa Waka, Kindai Nihon no Hansen-byō mondai to chiiki shakai [Modern Japan’s Problem of Hansen’s Disease and Local Communities]. Osaka daigaku shuppan-kai, 2011.

Kawase Naomi (Director) An, 2016.

Sukegawa Dorian, An [Sweet Bean Paste], Popura-sha, 2015.

Furubayaishi Kaigetsu (author) and Araragi Yukiko (consultant), Mugi baa no shima [Grandmother Mugi’s Island], Suirensha, 2017. 4 vols.

Sukegawa Durian, Sweet Bean Paste. Translated by Allison Watts. Oneworld Publications, 2017.

Kathryn Tanaka

After obtaining her PhD in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago in 2012, Tanaka joined the faculty at Otemae in 2014. Her main area of study is Hansen’s disease literature, in particular the ways in which community is created in literature by people who have experienced the illness. In addition, she is interested in minority experience of the illness and quarantine. She has published work on the depiction of women and children’s experiences. She is currently completing her book, Through the Hospital Gates: Community in Japanese Hansen’s Disease Literature.