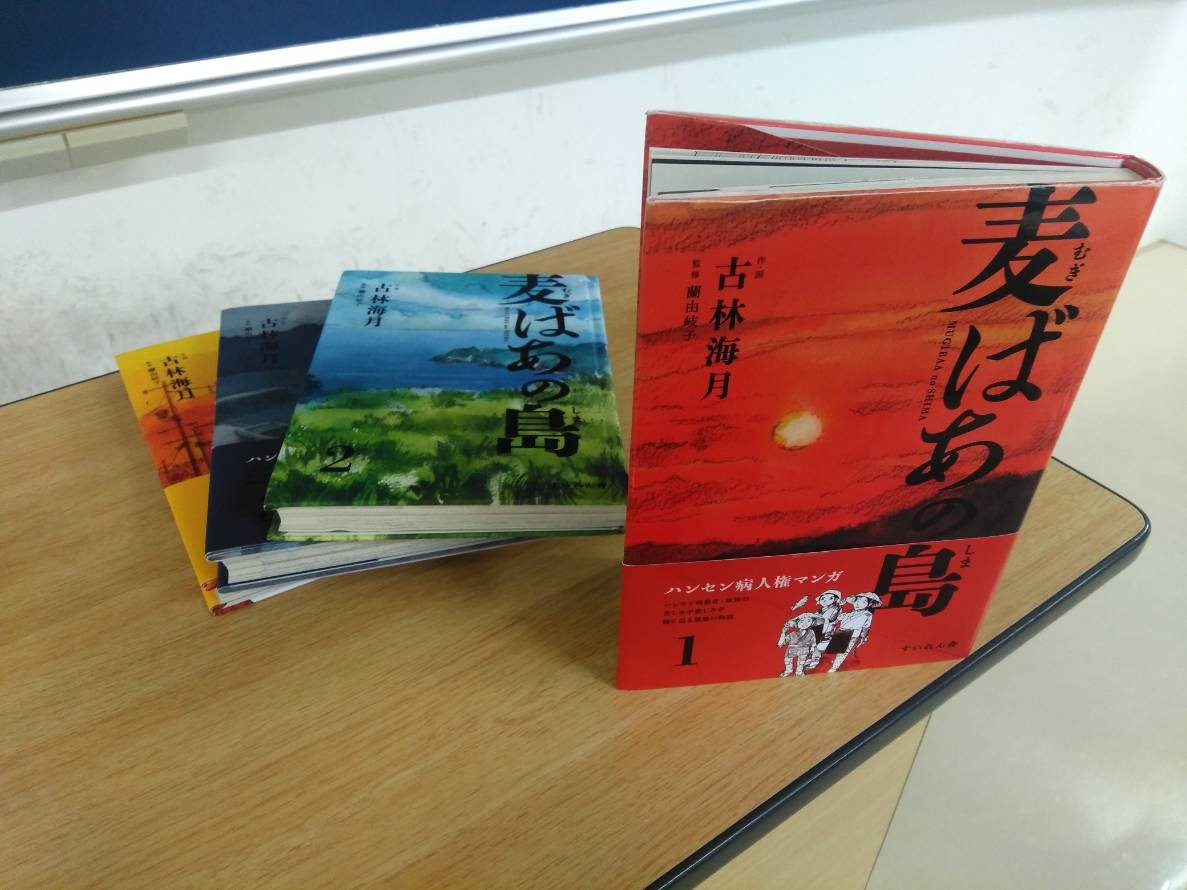

Hansen’s Disease and Family: Reflections on Reading and Teaching Mugi baa no shima (Grandma Mugi’s Island) Part2 /Kathryn Tanaka (Otemae University)

記事の和訳を読む >>

Otemae University students visiting Nagashima Aisei-en in Okayama Prefecture(May 2017)

In the manga series Mugi baa no shima, the inclusion of Satoko, who starts the series as a thoughtless university student dealing with an unplanned pregnancy and breakup, makes this manga a particularly interesting one to teach as students almost immediately relate to the issues raised through her character. I have used the book in a number of classes, and students have responded in a uniformly positive way; some have even asked to start a volunteer group to translate it into English so it can be read more widely.

Students also remark on the variety of issues that intersect with Hansen’s disease in this manga as an important point that allows them to approach the problems raised from multiple perspectives. One student remarked that while they have been to Nagashima Aisei-en, this manga offered “new information and a different experience” than what they had heard from the survivors’ talk at Nagashima. Another student remarked that they had read Hansen’s disease literature, visited Nagashima, and spoken to survivors themselves, but this manga “made it possible to combine the stories of multiple people into one.” Another student saw the manga as an important alternative to mass media accounts that frequently focused on lawsuits and men’s experiences rather than women.

The left:University students talking with the former president of the Residents’ Association of Aisei-en during a visit to Nagashima(May 2017)

The right:Students listening to residents of the Mokake community during their fieldwork in the area(August 2018)

Students also appreciated the attention to detail, both in the art and in the explanation and treatment of Hansen’s disease. Students with no knowledge of the illness felt they learned a great deal about Japanese history they did not know, and those who had some background knowledge felt the treatment reflected careful consideration of how to tell the story. This was also reflected in the fact that students invariably appreciate the fact that the images in the manga are graphic and fully depict the realities of the story, leaving little to the imagination—but they are not grotesque. One student commented that the text and the images are in harmony to make a complete story that has not been told in manga before.

In addition, students appreciated the detailed depictions of daily life, the references to smells, seasons, and the sounds (music to guide survivors who are blind floats through the scenes in the sanatorium, music echoes through the text, and city loudspeakers announce the time so children will go home for dinner, to give some examples a student commented upon). These details made the story seem more relatable and real to them.

Overall, students in general report two main features of this manga that they truly appreciate: First, they appreciate the way in which families are depicted throughout the text: the relations Mugi has with her natal family and how this relationship is changed with Hansen’s disease; Mugi and her husband; the two sisters; and the relationship of the sisters with Mugi and her husband. They appreciate the experiences of other characters who may not be the focal point of the series but whose stories are still fully developed. And, of course, students struggle in positive ways with the question of family and the absent children that haunt the text.

Second, students overwhelmingly appreciate the fact that the story is centered on women and their experience. While some male students remark that this made it uncomfortable for them at first, for many it became a way to understand not only human rights issues but also gender issues. For men in particular, the focus on female characters and their problems with fertility and family could be an important learning experience. One male student remarked: “They talked about the problems of the men too. But with the women, I didn’t consider their issues before. This was an important manga for me to read.”

The left:Students in Aisei-en, translating selections from the volume “The History of Okucho,” which details the history of Nagashima and the Mokake community on the opposite shore(August 2018)

The right:At Nagashima Aisei-en, students receive advice from the Residents’ Association president on their translations of the website and survivor testimony(August 2016)

Broadly speaking, these accounts, through their structure as a survivor relating their experiences to an adopted family, serve to make the stories of Hansen’s disease part of Japan’s cultural and historical narrative. Through stories such as Mugi baa no shima, the local, individual experience of Hansen’s disease is retold from new perspectives and connected to other social issues. In that sense, such novels are an act of legacy-making and a way of incorporating individual experiences of Hansen’s disease into larger stories of human rights and family. This manga is an important part of a new history of Hansen’s disease, launched by scholars such as Hirokawa Waka that considers the multiplicities of survivor experiences and the connections of individual experiences to national narratives. To paraphrase my student, it is something we should all read.

Arai Yuki, Kakuri no bungaku: Hansen-byō ryōyōsho no jiko hyōgen-shi [Literature of Quarantine: A History of Self-Expression in Hansen’s Disease Sanatoria]. Shoshi arusu, 2011.

Araragi Yukiko, “Yamai no keiken” wo kikitoru: Hansen-byō-sha no Raifu Stori [Hearing the “Illness Experience:” Life Stories of Hansen’s disease survivors] [New Edition], Seikatsu shoin, 2017.

Hirokawa Waka, Kindai Nihon no Hansen-byō mondai to chiiki shakai [Modern Japan’s Problem of Hansen’s Disease and Local Communities]. Osaka daigaku shuppan-kai, 2011.

Kawase Naomi (Director) An, 2016.

Sukegawa Dorian, An [Sweet Bean Paste], Popura-sha, 2015.

Furubayaishi Kaigetsu (author) and Araragi Yukiko (consultant), Mugi baa no shima [Grandmother Mugi’s Island], Suirensha, 2017. 4 vols.

Sukegawa Durian, Sweet Bean Paste. Translated by Allison Watts. Oneworld Publications, 2017.

Kathryn Tanaka

After obtaining her PhD in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago in 2012, Tanaka joined the faculty at Otemae in 2014. Her main area of study is Hansen’s disease literature, in particular the ways in which community is created in literature by people who have experienced the illness. In addition, she is interested in minority experience of the illness and quarantine. She has published work on the depiction of women and children’s experiences. She is currently completing her book, Through the Hospital Gates: Community in Japanese Hansen’s Disease Literature.